Four Western Surveys and the Romance of the Wild West

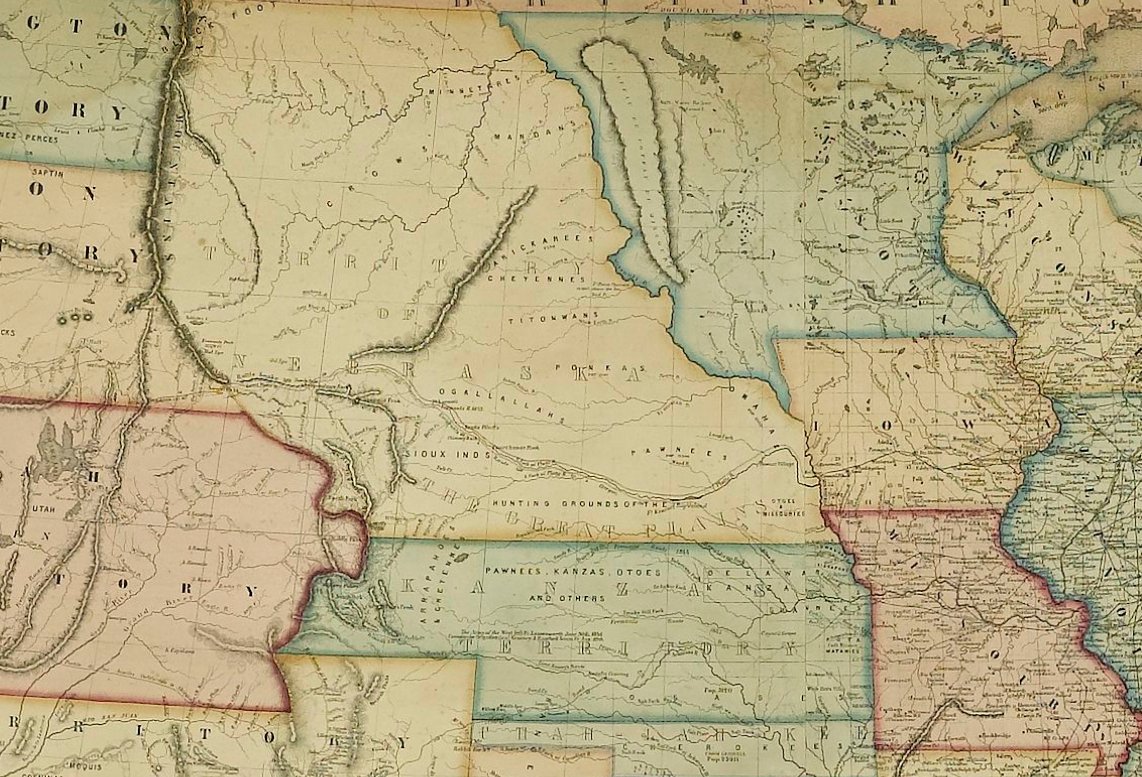

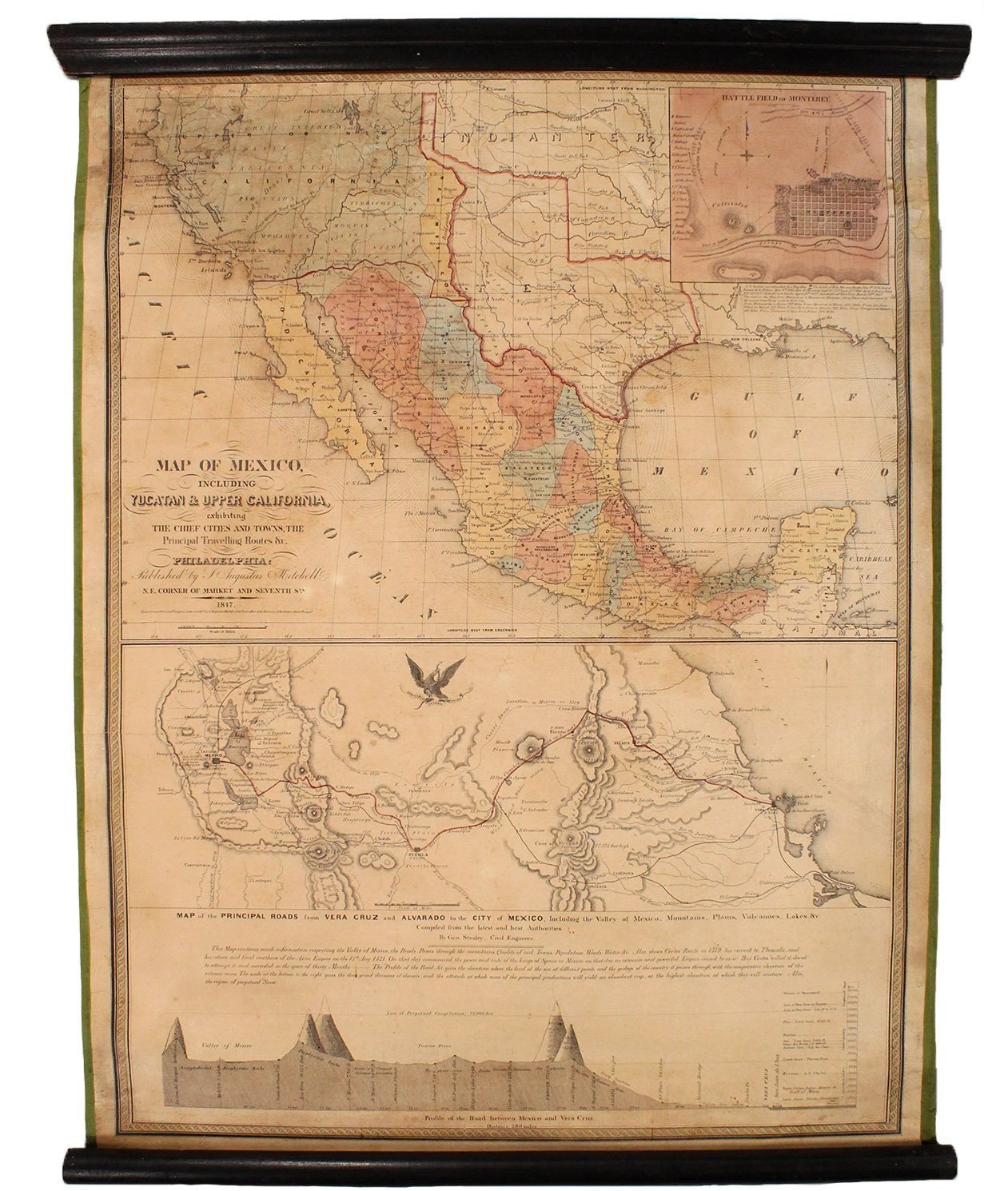

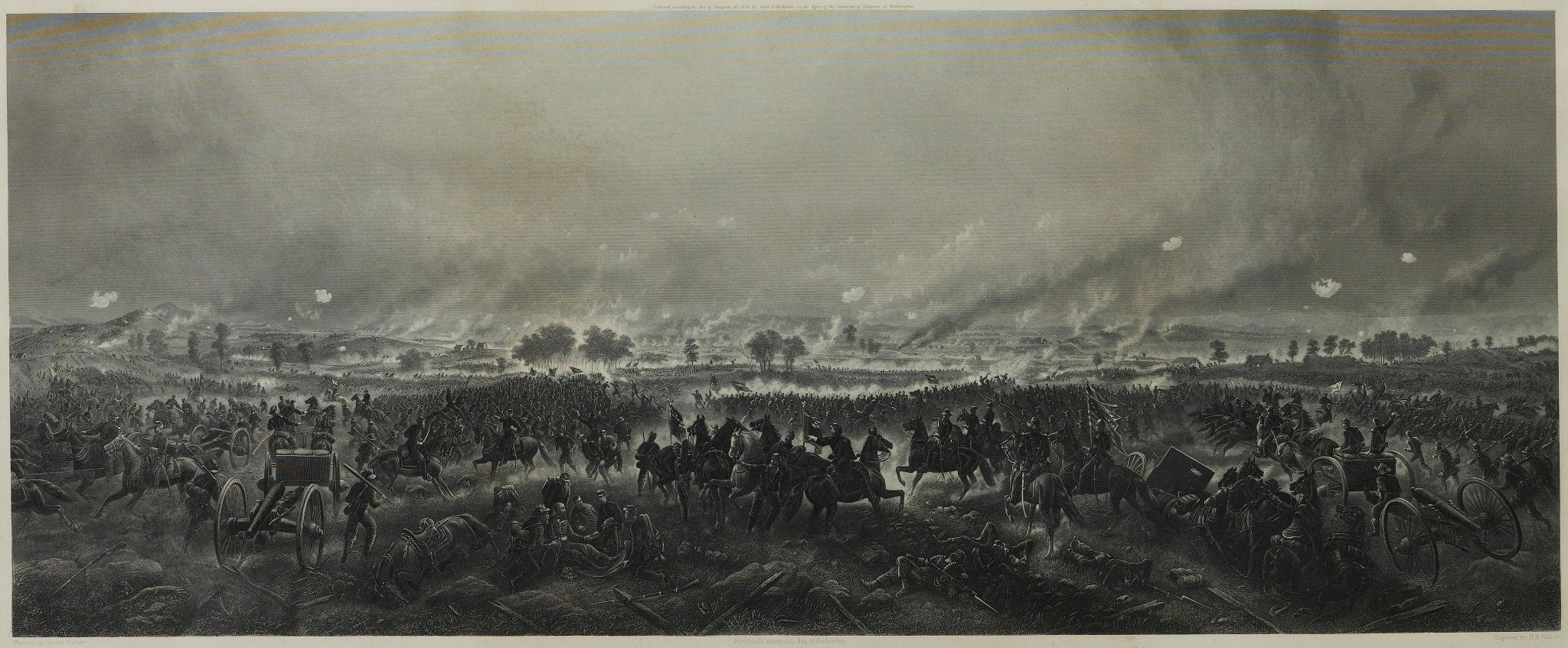

In the years preceding the Civil War, early U.S. Government-funded exploration, land acquisition, and the discovery of gold in California made the nation keenly aware of the promise and potential of western land. But the Civil War highlighted how inadequately the country was surveyed, as those fighting in the western theater struggled to move troops and supplies over unknown terrain. After the Civil War ended, surveying resumed with new vigor.

The national government turned its attention to the settlement of its western territory and exploitation of the continent’s mineral and geological wealth. Because the environment of the West differed significantly from that of the East, explorers were charged with identifying natural resources and assessing the utility of the land for farming, mineral extraction, railroad routes, military posts, and human settlement.

Scientists, geologists, and military engineers organized a group of experts to travel through the West, mapping and cataloging the land and its resources. Between 1867 and 1879, Congress authorized and funded four significant surveys, under four leaders: the Powell Survey, under John Wesley Powell (1870–78); the King Survey, led by Clarence King (1867–78); the Wheeler Survey, under Lieutenant George M. Wheeler (1871–79); and the Hayden Survey, led by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (1867–79). The four surveys were later consolidated into the nascent United States Geological Survey (USGS).

The King Survey explored the area along the fortieth parallel from northeastern California, through Nevada, to eastern Wyoming. His survey followed the sites of the proposed Union Pacific Railroad. Powell explored the Rocky Mountains in Colorado and eastern Utah and became convinced that the unknown canyonlands to the southwest could best be explored in boats. He embarked on a three-month river trip down the Green and Colorado rivers, which was the first official U.S. government-sponsored passage through the Grand Canyon. In 1872, Congress granted Wheeler $75,000 to map the area west of the 100th meridian on a scale of eight miles to the inch, an undertaking that Wheeler estimated would take fifteen years to complete. His main objective was to obtain data for a military map and to survey the possibility of a wagon road and select sites for military posts, including the area south of the Central Pacific Railroad in eastern Nevada and Arizona.

Hayden's Geological and Geographical Atlas of Colorado and Portions of Adjacent Territory, First Edition of Twenty Maps, 1877. LINK.

Yet the Hayden Survey was the largest and best funded of the four major surveys. Hayden wrote that he felt a comprehensive survey of Colorado would “yield more useful results, both of a practical and scientific character. . . . The prospect of its [Colorado’s] rapid development within the next five years, by some of the most important railroads of the West, renders it very desirable that its resources be made known to the world at as early a date as possible” (Hayden 1874, 11). Hayden’s scientific research made Colorado the most intensively studied place in the entire West, with the possible exception of California. His surveys and the resulting data output created an unparalleled number of publications, the most significant being the Atlas of Colorado.

(Interior details of) Hayden's Geological and Geographical Atlas of Colorado and Portions of Adjacent Territory, First Edition of Twenty Maps, 1877. LINK.

The Atlas of Colorado was well received in the scientific community. An August 1878 Geological Magazine review by T. Oldham celebrated:

“We have the results of four years’ labour (1873-74-75-76) produced and published in a finished site in the year 1877! And such four years of labour as these must have been! An area exceeding that of Ireland, in most parts inaccessible, everywhere difficult to travel in, open to disturbances, for fears of disturbances, from unsettled Indian tribes, where everything had to be carried with the observer, and he thrown entirely on his own resources, and such limited aid as he could bring with him; such an area has been triangulated, measured, physically examined, and mapped; its drainage carefully determined, its economic and agricultural divisions noted, and its geological structure carefully investigated. We have no hesitation in saying Prof. Hayden may justly point to this as a success, rarely ever approached, probably never equaled. And may justly recount with pride the names of those few who have so ably and so untiringly carried out his wishes.”

In addition to the annual reports of the surveys, government explorers and their team members disseminated information to the east coast about western environment and geology by lecturing, publishing in popular journals, writing tales of their harrowing survey adventures, and giving interviews to newspapers. They also provided entrepreneurial publishers with images and maps for duplication on stenographic cards and chromolithographic print sets. These published accounts helped incite a Western fever along the east coast populace, turning many of the explorers into popular celebrities.

1881 Hayden View of "The Twin Lakes - Lake Fork of the Arkansas, Showing the Great Moraines." LINK.

One such example is Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, who joined Major John Wesley Powell and a crew of scientists on Powell's second Colorado River expedition into the Grand Canyon in 1871. Dellenbaugh served as the expedition's artist and assistant topographer and helped to prepare the first map of the Grand Canyon. Thirty-seven years later, in 1908, Dellenbaugh published A Canyon Voyage. The book was a first-person account of the survey and is richly illustrated with a color frontispiece and numerous plates from original photographs taken while on his Colorado River expedition, included to catch the eye and imagination of his readers. The book was written for, and very well received by, a public hungry for accounts and images of the Grand Canyon.

The wide public interest reflected the transformation of American attitude toward the West. Previously, the West had been a place to cross over on the way to the Pacific coast or a place of uncharted mystery, yet fearsome and dangerous in either case. Yet new photographs, canvasses, and prints conveyed the monumental size and geological complexity of the region and enticed viewers to experience its scenic splendors themselves. This was an extension of the Romantic worldview, where the individual sought out unspoiled wilderness to experience nature’s power first hand. As once tourists had flocked to Niagara Falls to revere the sublime and beautiful vista, western sites such as Yosemite and Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon became popular vacation destinations.