How D.C. Came to Be

Today we delve into the details of how D.C. came to be! From early parameters for a capital city up through the Frenchman that devised a city plan, here is how the District of Columbia was formed.

Following the Revolutionary War

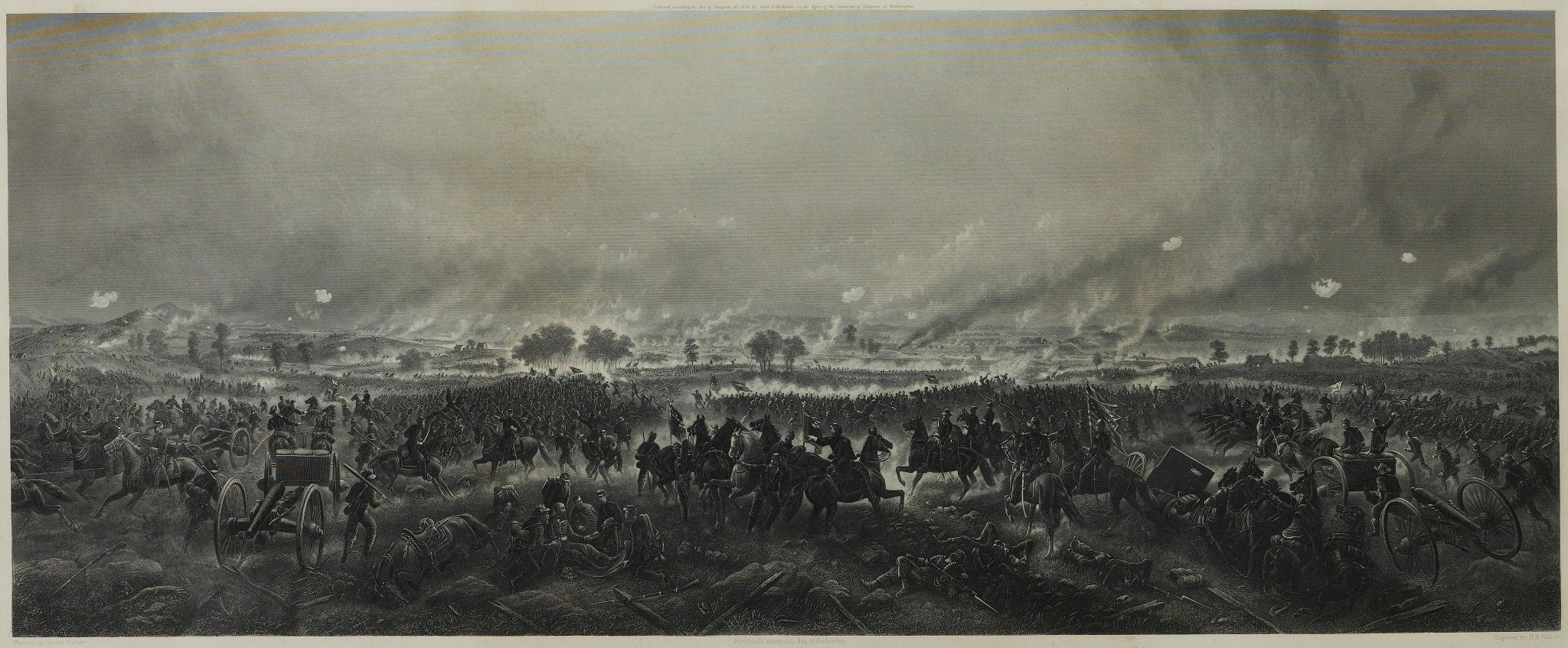

Washington D.C. as we know it today has grown and changed from the once swamp land that it was. After the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, when American colonists declared their freedom from the oppressive Great Britain and defined a separate, free nation, the need for a capital was apparent. However, the official site of the American capital was not established upon the signing of the Declaration, and the matter was very much unresolved for years afterwards.

Members of Congress negotiated the site of the capital for years following the birth of the nation. Many disagreed over the proposed capital land. Northern states with Alexander Hamilton backing them expected the new federal government to be positioned in a northern location to assume the Revolutionary War debts, while Thomas Jefferson and southern states wanted the capital to be placed in a location friendly to slave-holding agricultural interests. The location would determine the government's role in all of this and while the newly formed nation boasted its freedom, the discussion to determine this decision was teetering on disarray.

The Location

It was none other than newly appointed President George Washington to choose the exact site along the Potomac and Eastern Branch (today Anacostia) Rivers for the District of Columbia. The City of Washington was officially founded in 1790, after the states of Maryland and Virginia ceded land to the capital. This provided a compromise for the northern and southern state inhabitants. On July 16, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which created a permanent seat for the federal government. The Residence Act provided a location for the capital "at some place between the mouths of the Eastern Branch and the Connogocheague," which was made possible in conjunction with the Compromise of 1790.

President George Washington formally announced the location and approximate size of the capital, measuring 10 miles on each side in a diamond shape centered on the convergence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers. Following the official announcement, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a Frenchman, was employed to develop a plan for the city itself while Andrew Ellicott was to conduct a topographical survey.

The Frenchman Who Designed the City

L’Enfant was born in Paris but traveled to the United States when he was 23 years old to fight in the American Revolutionary War. He served under Major General Lafayette as a military engineer and closely identified with America after his time spent there. L’Enfant established a reputation as an established artist and engineer and was later hired by George Washington to design the capital plan after he presented an innovative and bold outline. L’Enfant used his French and European architectural and structural style to modernize the American city. His vision included grand boulevards and wide public squares. The centerpiece of his plan was the center “public walk,” known today as the National Mall. “Inspired by the topography, L'Enfant went beyond a simple survey and envisioned a city where important buildings would occupy strategic places based on changes in elevation and the contours of waterways” (Fletcher).

L’Enfant’s idea for the present day National Mall embodied the European model that was adjusted to compliment the newly formed American city’s culture. The large scale of the National Mall was in line with the French style, yet differed greatly due to its accessibility: "’The entire city was built around the idea that every citizen was equally important...The Mall was designed as open to all comers, which would have been unheard of in France. It's a very sort of egalitarian idea’” (Fletcher).

1792 Official Plan

L’Enfant, as innovative as he was, was reportedly quite difficult to work with. He had very elaborate ideas and a very strict unwillingness to compromise. In February of 1792, Andrew Ellicott reported that L’Enfant had refused to provide him with the original plan to send to print production. George Washington eventually dismissed L’Enfant from his position and passed the entirety of the project on to Ellicott in 1792.

Ellicott used his notes on L’Enfant’s initial designs for the basis of much of the plan. The 1792 plan, being the first official and documented plan of the City of Washington, embodies much of L’Enfant’s original view for the city. Ellicott kept with L’Enfant’s European model, with large streets and public squares that created a dramatic cityscape. Ellicott’s final design was sent into print production in 1792 out of both Philadelphia and Boston to facilitate the sale of land in the new capital.

Since then, the plan for D.C. has shifted and changed. While L'Enfant's design with Ellicott's rendering was an excellent work on which to base the capital, the city needed a lot of work. However, the 1792 plan provided a detailed scale and elaborate design that would make up the many streets and monuments in the City of Washington.

Fletcher, Kenneth, A Brief History of Pierre L’Enfant and Washington, D.C. Smithsonian.com, 30 April, 2008.