What Is a Lithograph and How Is It Made?

Since its invention in the late 18th century, Lithography has enthralled artists and the public alike but how exactly is a lithograph made? How is it different from other prints? Lithographs allowed for the advancement of 19th century commercial printing and are still used even today. Be sure to check out The Great Republic’s collection of fascinating lithographs!

WHAT IS A LITHOGRAPH?

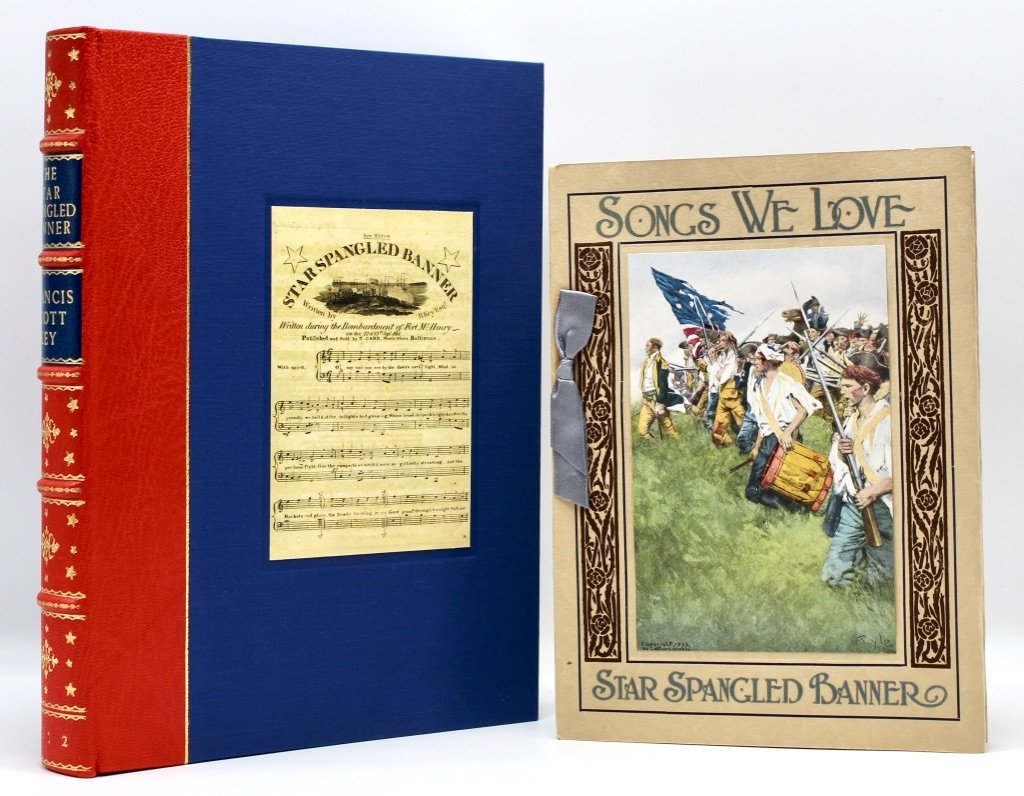

A lithograph is a type of print produced by pressing paper onto an ink and water-soaked stone to transfer an image. The name "lithograph" derives from Greek words “lithos” and “graphien” meaning “stone” and “write” respectively. An artist is able to write or draw directly onto a stone to produce an image that is softer and more detailed than etchings. Early lithographs are printed in black ink and hand-colored afterwards, but artists were soon able to produce color lithographs through a painstaking and highly skilled process. Alois Senefelder, a Bavarian playwright, discovered the technique in the late 18th century while trying to replicate his scripts. The medium quickly gained popularity and was adopted by artists such as Théodore Gericault and Eugéne Delacroix. By the 1880s, lithograph technology had grown and allowed for the difficult color prints and larger paper wildly expanding the commercial possibilities.

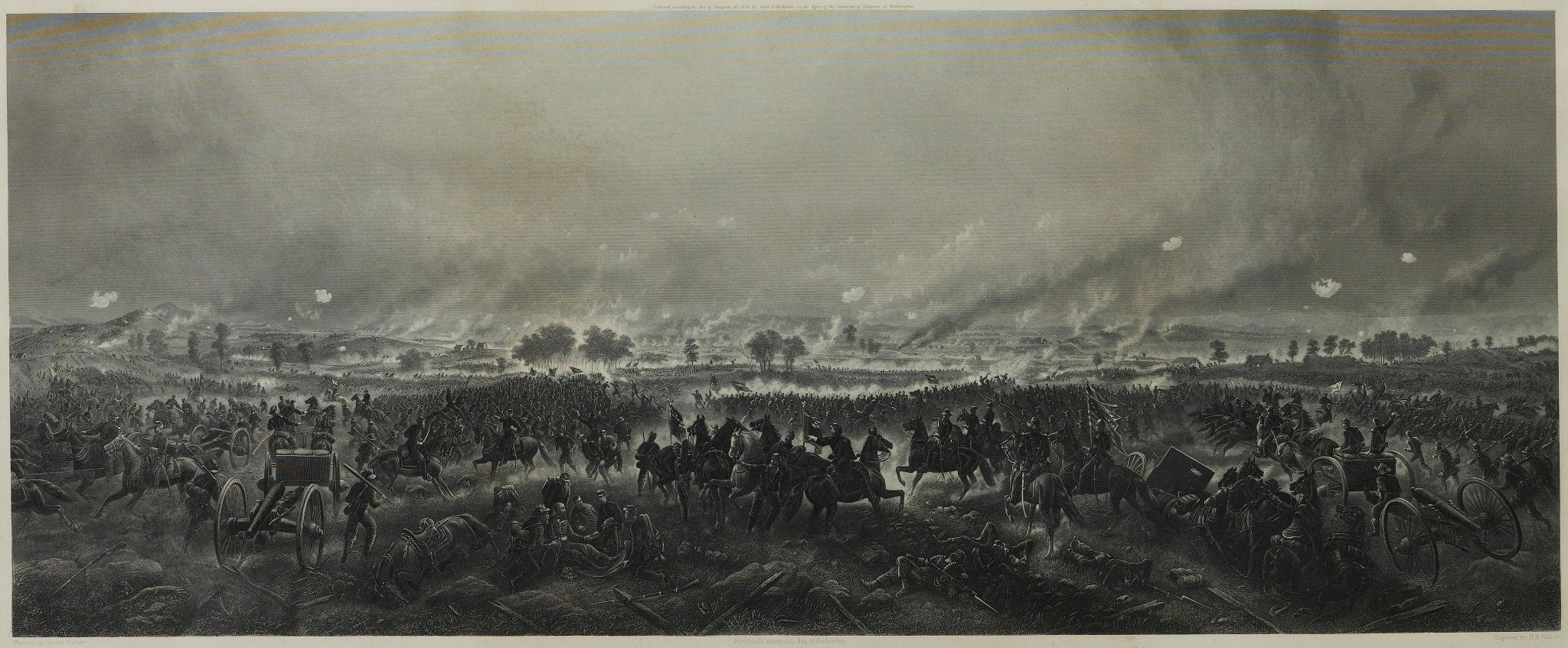

Looking closely, one can see the differences in the below lithograph detail images. The first is an uncolored 1846 lithograph, the second is a hand-colored 1842 lithograph, and the last is a 1908 chromolithograph printed in color.

THE PROCESS

Lithography utilizes the immiscibility of water and oil, or the incapability of combining the two materials. By conditioning some areas to accept oily printer's ink and other areas to accept water, the printer can delineate an image to transfer onto paper.

Step 1

An artist uses a wax pencil or “litho crayon” to draw directly onto a polished slab of limestone. As opposed to etching or engraving, this allows the artist to create a printed image that looks more similar to a drawing.

Step 2

Once the drawing is finished, the surface of the stone is treated with chemicals to bind the drawing to the stone and mark out the areas that will hold the ink. First rosin and talc are added on top of the image to help draw the oil down into the stone and “bind” the drawing to the surface. Then gum arabic and TAPEM are wiped onto the stone to help the blank areas accept water and the image areas to accept grease. This allows the blank areas to absorb moisture while repelling the lithographic ink. The original drawing is wiped away with a solvent called lithotine leaving only a trace of the original drawing. Finally, the stone is prepared to be inked by buffing asphaltum into the stone’s surface. The end result of this chemical treatment is to allow the oily ink to sit only in the area of the image while it is repelled by the blank, watery areas.

Step 3

Water is wiped onto the stone surface with a sponge and printer’s ink is rolled on. This step is repeated until the full image is visible again with all of its original details. By now, the ink sits in the image area, but no ink will stay on the blank areas.

Step 4

A dampened piece of paper is carefully laid over the stone. To distribute the upcoming pressure, a thick board is set on top to ensure an even print.

Step 5

The stone, paper, and board go through a litho press, applying enough pressure to ensure the ink transfers to the paper and does not omit any details. Finally, the paper can be carefully removed from the stone producing a mirror image of the original drawing.

COLOR LITHOGRAPHS

Originally, lithographs were monochromatic prints, using only black ink. If s/he desired a colored print, the artist would hand-color the image afterwards to create a final product. Eventually, printers were able to print in various colors but the effort and skill required proved to be a formidable task. To produce a color lithograph, a new stone had to be produced for each area of color and would need to match up perfectly with the other parts of the image. Furthermore, the paper must be aligned correctly when being laid down on each successive color’s stone. A daunting task, but the market for color lithographs produced constant demand.

In 1904, an American printer revolutionized printing yet again with offset lithography. Ira W. Rubel developed a method of printing the image twice: once onto rubber rollers and then onto paper. Called "offset lithography," the end result allowed prints to be made at an accelerated pace, lengthened the life of the original stone (or in more modern cases, a sheet of metal) since it is used only to print on the rubber rollers, and produced images that matched the original instead of mirroring.

ARE THEY COLLECTIBLE?

Yes, they are highly collectible. Most lithographs are produced in only limited quantities and the delicate nature of the paper typically means that not all of the lithographs in a print run survive the passage of time. Occasionally, artists will even sign their lithographs. Lithographs originally served as an affordable work of art for the middle class who could not pay for expensive paintings but have since become their own admired and valuable medium. Lithographs offered by The Great Republic are typically custom framed with UV filtering plexiglass and non-acidic matting to preserve these delicate but impressionable works for years.