Taking Back the South Pacific: Operation Cartwheel

On December 8, 1941, just hours after their attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese army turned their attention toward another American stronghold, the forces stationed in the Philippines, and attacked. All through December, Japan scored victory after victory, taking control of islands ranging from the Aleutians to the Philippines. In January 1942, Japanese troops overpowered an Australian garrison at Rabaul, on the southwestern Pacific island of New Britain. Rabaul became the centerpiece of Japan’s defense in the southwest Pacific. The base provided Japanese forces with the naval power, supplies, and reinforcements to control the sea lanes of the Southwest Pacific. It was also a nearly impregnable airbase and a haven for a large Japanese fleet of fighters and bombers.

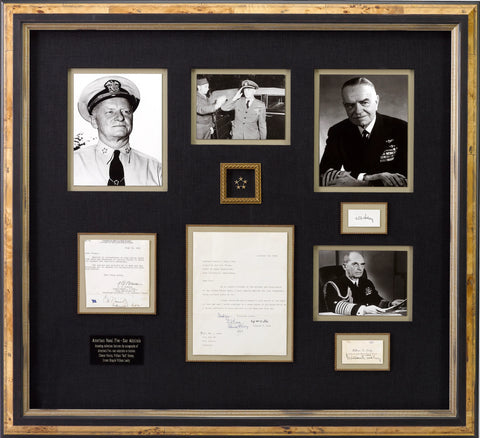

In the summer of 1943, Allied forces in the Pacific launched Operation Cartwheel, a series of amphibious assaults aimed at encircling Rabaul. First, Admiral Nimitz and his South Pacific forces would take Guadalcanal. General Douglas MacArthur would lead Allied troops in the approach of Rabaul from the southwest, through New Guinea and the southern Bismarcks. Meanwhile, Admiral William “Bull” Halsey would advance north through the Solomons.

Unlike the European Theater, where infantry and tanks were massed to sweep through Europe, the geography and size of the Pacific Theater required a different approach. The aggressive Allied strategy adopted in mid-1943 called for an “island-hopping” or “leapfrogging” strategy. The strategy was based on the belief that isolating Japanese forces would be just as effective as destroying them through direct attacks, and far less costly to Allied forces. Bases that were too heavily guarded were skipped over. Allied forces concentrated on attacking only select enemy bases while bypassing others with the hope that, cut off from their supply routes, the entrenched Japanese bases would "wither on the vine," as General MacArthur described it.

The Allied command landed their amphibious forces in key areas where they could disrupt enemy supply lines. On each island they captured, the Allies constructed air bases, allowing them to block any westward movement by the Japanese and extend their ability to attack deep into enemy territory. This tactic helped lay the groundwork for their next “hop.”

This type of coordinated approach to warfare emphasized the need for quick and highly mobile amphibious and air forces operating together, over vast distances. Although MacArthur regularly contended with the Navy and the Army Air Corps for resources, men, and command, he understood that an Allied victory in the Southwest Pacific depended on Navy cruisers, destroyers, and amphibious vehicles, and on Air Corps fighters, bombers, and transports. “He never put his men ashore without seeking the views of amphibious commandeer Daniel Barbey, did so only when they were protected by Adm. Thomas Kinkaid’s ships and never fought a battle without the protection of Gen. George Kenney’s bombers” (Perry, 2014).

This type of coordinated approach to warfare emphasized the need for quick and highly mobile amphibious and air forces operating together, over vast distances. Although MacArthur regularly contended with the Navy and the Army Air Corps for resources, men, and command, he understood that an Allied victory in the Southwest Pacific depended on Navy cruisers, destroyers, and amphibious vehicles, and on Air Corps fighters, bombers, and transports. “He never put his men ashore without seeking the views of amphibious commandeer Daniel Barbey, did so only when they were protected by Adm. Thomas Kinkaid’s ships and never fought a battle without the protection of Gen. George Kenney’s bombers” (Perry, 2014).

The air, land, and naval operations of Operation Cartwheel eventually isolated Rabaul in March of 1944. Allied leadership decided to bypass the Japanese base, and not engage in conventional battle with the heavily entrenched enemy force. In doing so, a potentially costly land battle was avoided. The Allies trapped approximately 110,000 Japanese soldiers and airmen on Raboul, cutting them off from supplies and from the rest of Japan’s island positions in the Pacific. Without the crucial garrison, Japan could neither threaten Australia nor continue its South Pacific offensive. Operation Cartwheel was a giant success and now serves as an excellent study of the “island-hopping”strategy.