The Promotion of National Parks with Railroad Posters

At the beginning of this century, western national parks were inaccessible to most Americans, both geographically and financially. To help prove their potential as public spaces worth protection and funding, the parks had to attract visitors to areas they knew nothing about. Geography also posed a major impediment. The vast majority of the population resided in the East, yet America's first national parks were located in the West. A major concern for those seeking to increase park visitation was how to transport tourists to the parks, in addition to convincing them that the trip was worthwhile. Western railroad companies stepped in and offered a solution to both problems.

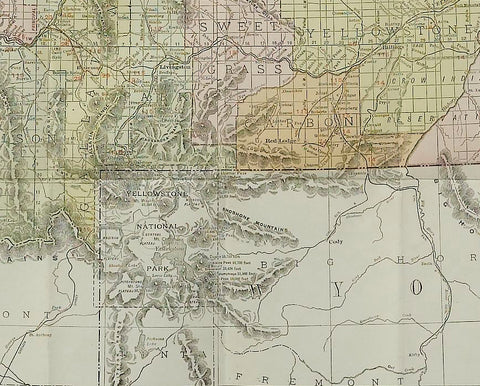

Many railroads built transcontinental lines in exchange for land from the federal government. Because the railroads profited by selling this land to settlers, they were avid supporters of western development and agriculture. In addition, by helping to build a population base in sparsely settled areas, railroads were creating a built-in, permanent market for their freight and passenger services. The establishment of Yellowstone National Park and, after the turn of the century, Glacier National Park fit perfectly with the railroads' promotional strategies. Tourist traffic promised additional profits, and the railroads were eager to join the cause.

The Northern Pacific became the first railroad to ally itself closely with a specific park. In 1883, the Northern Pacific Railroad completed its line across Montana and designated Livingston, a small railroad town approximately fifty miles north of Yellowstone National Park, as the point of embarkation for park-bound tourists. It began aggressively promoting the park, using Thomas Moran’s epic paintings to attract riders. The Northern Pacific set the course for other western railroads to follow. By 1910 the Southern Pacific had adopted Yosemite, the Santa Fe claimed the Grand Canyon, and the Great Northern was determined to secure Glacier's reputation as the "Crown of the Continent."

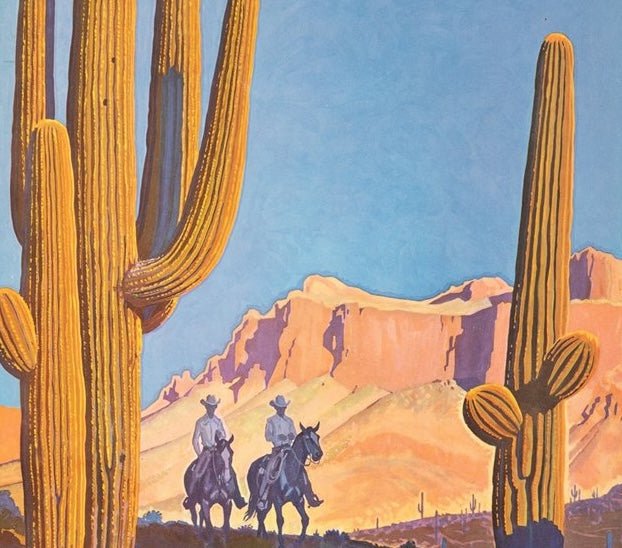

The railroads commissioned prominent painters to tour the West and paint its grandest attractions. These works were displayed in public buildings throughout America to entice would-be travelers with the possibilities of a western vacation. Massive oil paintings of glaciers, geysers, and mountain peaks were exhibited in hotels, bank lobbies, and other highly visible locations. The paintings proved exceptionally powerful in communicating the drama of the western landscape and were highly effective in winning public support for the national parks.

Yet original paintings could be viewed by only a relatively few potential tourists. To reach greater numbers of people, railroads transformed these paintings into a variety of promotional formats. Commissioned paintings were reproduced on postcards, souvenir playing cards, railroad timetables, and dining car menus. But the most effective tool for inspiring wanderlust among the masses was the travel poster.

Advances in printing technology made the mass production of large, full color posters possible. Posters were easily displayed in depots and ticket offices, in numbers far greater than was ever possible with original paintings. Countless more passersby were now exposed to such scenes as Moran's The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and informed that the railroads could take them there.

These railroad posters introduced the wonders of western parks to many Americans and convinced them that the best way to travel there was by train. As important as the scenery were the depictions of the new trains, powerful enough to traverse the geography and weather of the snow-capped Rockies, arid southwest, and more. Later advertisements even boasted the train amenities, like dining rooms and sleeping cabins, making the train trip equally as enticing as the destination.