Understanding the Value of Facsimile Documents

We offer a variety of engraved documents that are facsimile copies of the originals. We often get asked, “If it is a facsimile, then why is it valuable?” This question comes up a lot, and we are here to answer it! Read more in this week’s blog, which explains the importance and value in facsimile copies of famous documents.

Facsimile Engravings

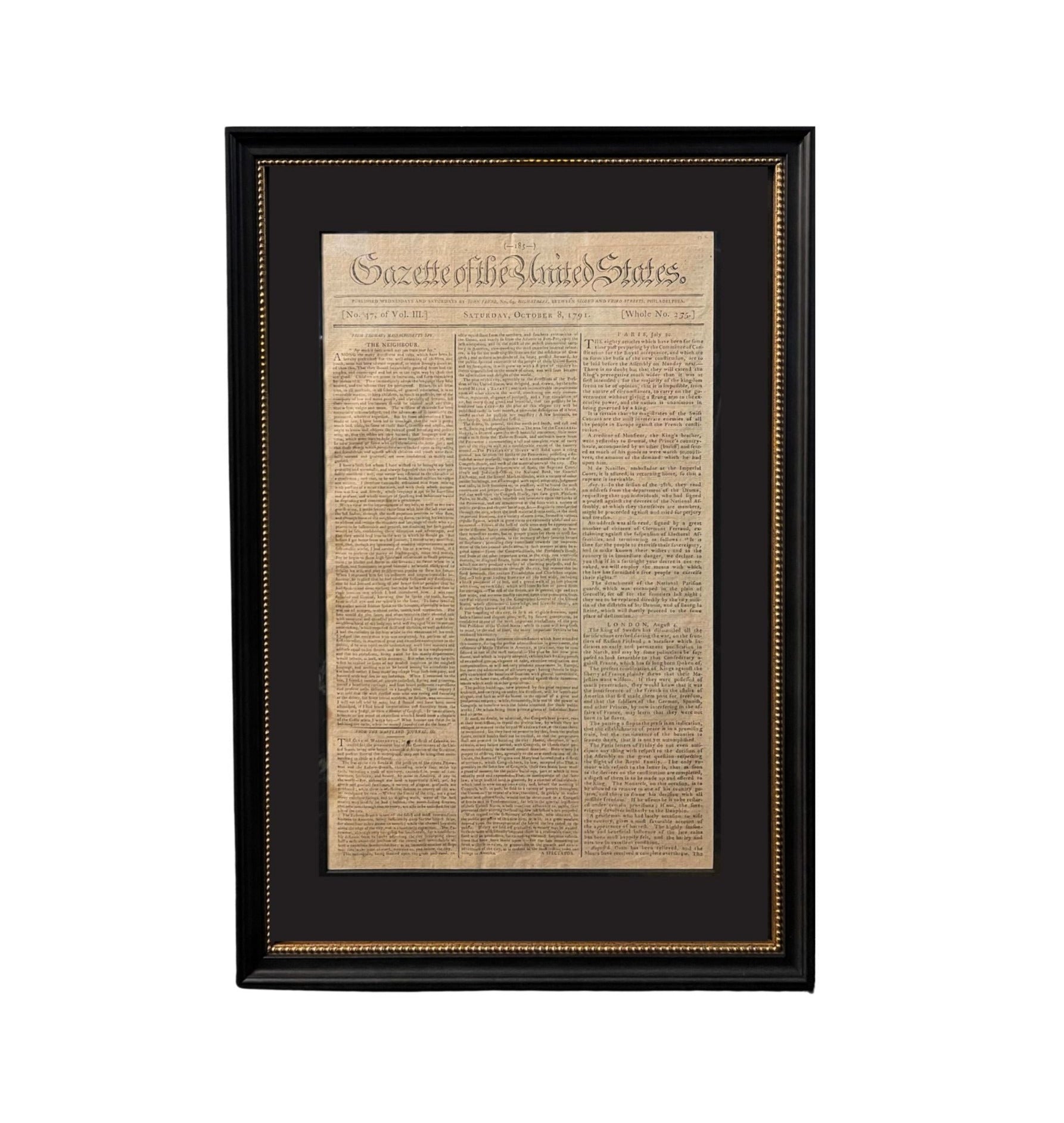

To start, it is important to understand that the facsimile documents we are talking about are not contemporary. They are old, original documents in their own right. Often times, engravers and calligraphers took advantage of the fact that most of the country had not examined a famous and influential document, such as the Declaration of Independence. It seems extraordinary that the Declaration of Independence was unknown to most Americans, as the text was so central to the founding of the nation. Several engraving entrepreneurs set out to bridge the gap by printing reproductions of the document, and others of similar importance.

Early broadsides of documents often hung in public places, such as nineteenth-century schoolhouses. This way, the words written by the American Founding Fathers could be taught to a broader audience, including the youth. Documents were sold, sometimes to public officials, and sometimes to raise money for a greater cause. An example is given with our 1863 facsimile document of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Emancipation Proclamation

President Lincoln signed the final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st, 1863. Lincoln then donated the original final draft to the Northwestern Sanitary Fair in Chicago in 1863, to be sold to raise money for medical support of the soldiers. Thomas B. Bryan purchased the document for $3,000 and in turn donated it to the Soldiers' Home in Chicago. Bryan commissioned lithographer Edward Mendel to create facsimile broadside printings of the original document. The sale of these broadsides funded the United States Sanitary Commission and the Soldiers' Home in Chicago.

The original Emancipation Proclamation draft signed by Lincoln was later destroyed in the Chicago fire of 1871, thus leaving broadside printings as the only real, original records of the document. This final draft of the Emancipation, shown above, portrays the edits that were made on the original document. It also includes an engraved portrait of Lincoln with a facsimile signature at the bottom. It is detailed and intricate, but not overly elaborate that it strays too far from the original.

Beneath the Proclamation text is a statement detailing the intent for the sale of the facsimiles. The statement was signed by Thomas B. Bryan, President of The Soldier's Home, Chicago, Illinois and reads: “This publication is undertaken in behalf of the General Treasury of the United States Sanitary Commission, and also to create a fund for the erection and maintenance of a permanent home for our sick and disabled soldiers. Purchasers of this fac-simile of the Proclamation of Freedom will thus invest that immortal instrument with a new interest, as contributing to noble institutions which shall prove a just tribute of a Nation’s gratitude to her patriot sons.” We have written proof to explain why these documents were produced and where and why they were sold.

Declaration of Independence

Interestingly enough, documents such as the Declaration of Independence were not really understood by the broad American population at the time. Engravers and calligraphers took advantage of the fact that there was a market for facsimile reproductions. The first to do so was a writing master named Benjamin Owen Tyler, who created a calligraphic version of the Declaration and published it in 1818, recreating exactly the signatures of the signers as they appeared on the original. His craftsmanship and attention to detail would be later emulated by aspiring artists and calligraphers. Three other broadside printings of the Declaration were issued in 1818 and 1819, each containing ornamental borders or illustrations. These were followed in 1820 by the present printing, shown below.

1820 Declaration of Independence Broadside

By Eleazar Huntington

This rare example of the Declaration of Independence, shown above, is known as the "Huntington" edition. Eleazar Huntington was a master calligrapher and engraver who intentionally retained the “feel” of the original Declaration, while incorporating new styles of presentation into his engraving. Huntington used Benjamin O. Tyler's earlier 1818 facsimile Declaration as a model and insured that the famous signatures were faithfully reproduced without unnecessary embellishment. Huntington's engraver mark is even visible at the bottom of the page.

Draft of the Declaration

Facsimile reproductions were also done of other documents, including drafts. Charles Toppan (1796-1874) was a noted early antiquarian and the first to produce an engraved facsimile of Thomas Jefferson’s manuscript of the Declaration. He produced an engraved facsimile of the draft that Jefferson created of the Declaration. All that remains of the first handwritten draft is a cut fragment that was found behind a picture frame in 1947. The small portion of Jefferson’s handwritten draft is housed in the archives at the Library of Congress, with the rest of the Jefferson Papers Collection. The fragment shows the process Jefferson went through when writing the Declaration of Independence; there are many of crossed out sections, scribbles, and even errors. This facsimile copy reproduces all of those elements accurately and completely.

1829 Draft of the Declaration of Independence

By Charles Toppan

The majority of the 86 edits seen on this copy of the draft above are in the handwriting of John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. At a later date, most likely in the 1800s, Thomas Jefferson went back to his draft and annotated in the margins with the changes suggested by Adams and Franklin.

Toppan’s engraved draft is an incredible piece of history from 1829. Since only a fragment of the original draft is left, the engraved facsimile tells its story. After many partnerships throughout the nineteenth century, Charles Toppan & Co. would engrave many notable pieces of American history. Today, many of his works are held in the Library of Congress and the U.S. Postal Museum.

What Facsimiles Offer

Facsimile documents offer us a great deal of information, especially when the original documents are lost or in worse condition. The fact that facsimile copies were hand engraved is a feat in itself, as many of the best and brightest artists of the time were executing the documents.

Calligraphers and engravers took the chance at engraving facsimile documents when they saw a place in the market for them. The works of art they created were accurate, detailed, yet also all their own. Facsimile documents offer us a look at the world from the time when they were produced and offer excellent examples of exquisite craftsmanship.